As a child growing up Portuguese American in one of the many immigrant neighborhood of Fall River, MA, I vividly remember that it didn't take much to earn great scorn and ridicule from our Anglo friends and neighbors.

Even the French Canadians, the immigrant wave which had immediately preceeded us, could not resist the ancient game of the human enterprise: "turnabout is fairplay." They exacted the prejudice which had been done to them on us - just as the Irish immigrants had exacted shame and ridicule for being the latest "greenhorn" immigrant - and so on in a most unfair turn of events.

I can still hear the cruel laughter of children and their parents about the way we dressed, the shoes we wore, and the curious description of my thick, tighly waved, jet black hair as "kinky." It wasn't until I was a teenager and heard someone describe an African-American's hair that I got the full imact of this particular taunt.

As Portuguese and Azorean people, we were darker than the previous immigrants, and our "foreign" language made us not exotic, but "strange" - and therefore, ripe for ridicule and oppression - and associated with "the least of these" other outcasts.

One custom brought us more prejudice than others - my grandmother often took us on picnics. No, that wasn't the "unusual" part. It was where she took us on picnics. We went to the cemetery.

Yes, I said cemetery. As in, the place where the dead are buried.

Yes, I said cemetery. As in, the place where the dead are buried.There, at the cemetery, amid baskets filled with hot sausage sandwitches and served on hard rolls, red wine (a special newly fermented grape juice made just for kids), and thick slices of Portugese Sweet Bread lathered thick with sweet, creamy butter for dessert, my grandmother would tell us stories - wonderful stories about the person who had died. She had had twenty pregnancies and twenty two children (two sets of twins), some of whom died at birth, others of childhood diseases, and "Augie" - her first born son who had died in a textile mill accident.

Only 15 of her children lived to adulthood, but the little ones who had died were very much alive to her as the ones I knew to be my aunts and uncles.

There was a wonderful continuity to my gradmother's world. The dead were not "the living dead" - like some spooky horror movie that always weirded out my Anglo friends - but those who had "passed on" to another realm, one with which my grandmother seemed to be in constant communication.

The "dead" also included new babies who had not yet "crossed over" and come to live with us. My grandmother taught that we met them all - those who had passed on, those who were here present and those yet to come - at the Eucharistic table.

Which was why, she said, we called it "Holy Communion." Not only was Jesus fully present to us, but also there, around that altar, was the "mystical sweet communion" of life eternal in Christ Jesus.

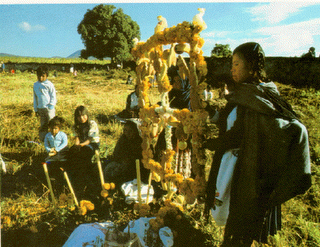

Today, Mexicans celebrate "Dia de los Muertos" - the Day of the Dead. That celebration will vary widely from city to city, and rural area to rural area. It is a complex feast which dates back to their Culipan, Oaxacan and Zapotec ancestors who honored the dead - much in the same manner as my grandmother.

Indeed, in Mexico, children are the focus of the celebration of Dia de los Muertos - because they are closest to the saints and they are the future.

Although I am unaware of a specific holiday, my African and Asian friends seem to have a very similar understanding of "the ancestors" - not as the "living dead" but as those who live on in another realm - with whom communication is constant and central to their understanding of who they are.

I have found it a rare thing for Episcopalians to talk about this aspect of "Holy Communion" outside of a Eucharistic theology. For the most part, All Saints Sunday is a fairly sanitized service. Perhaps a necrology is read. Perhaps the Taize chant "Jesus, Remember Me" is sung.

But Episcopalians have nothing like Dia de los Muertos. We remain "up in our heads" -disdainful of anything we can't reason or prove. We like our time linear, thank you very much, so we can mark it off and control our sense of reality. Indeed, we like our celebrations "meet, right and proper" - and, preferably under 60 minutes.

I've never heard an intelligent discussion of the possibility of another realm of reality from a pulpit in the Episcopal Church - except for those oriented toward justice who talk about "the kin-dom of God."

Granted, I've not been to every Episcopal Church in the United States, but, after 20 years of ordained service, I HAVE been around a bit. Never have I heard a sermon which addressed my grandmother's notion of "the ancestors." However, I imagine that in some of the Hispanic congreagations with Mexican influences, what was once "pooh-poohed" if not outright excluded, more religiously ethnic celebrations like this might well be gaining some popularity.

All that being said, I haven't heard this discussed anywhere in our post modern American culture. For the most part, "thoroughly modern Americans" of Western European origin seem only to have a firm grasp on the obvious. With the exception of television programs about "the occult" or fantastic stories about houses haunted by poltergeist, this sort of concept of "the ancestors" - past and yet to come - is simply not part of our cultural heritage.

At least, I don't hear it talked about in polite conversation, much less written in any of our modern literature.

Except for this. It's from one of my all time favorite books: A Winter's Tale by Mark Helprin. Each time I read it I marvel not only at the breataking beauty of its prose, but how it expresses to my now almost thoroughly Westernized (and sanitized) mind, an intellectual Western-European reasoning for the existence of "things seen and unseen."

I append it here for your prayerful consideration on this "Day of the Dead" with great thanksgiving to my Grandmother and the richness I have from her presence with me this day - and always.

From: A Winter's Tale:

Nothing is random, nor will anything ever be, whether a long string of perfectly blue days that begin and end in gold dimness, the most seemingly chaotic political acts, the rise of a great city, the crystalline structure of a gem that has never seen the light, the distributions of fortune, what time the milkman gets up, the position of the electron, or the occurrence of one astonishingly frigid winter after another.

Even electrons, supposedly the paragons of unpredictability, are tame and obsequious little creatures that rush around at the speed of light, going precisely where they are supposed to go. They make faint whistling sounds that when apprehended in varying combinations are as pleasant as the wind flying through a forest, and they do exactly as they are told. Of this, one can be certain.

And yet there is a wonderful anarchy, in that the milkman chooses when to arise, the rat picks the tunnel into which he will dive when the subway comes rushing down the track from Borough Hall, and the snowflake will fall as it will. How can this be? If nothing is random, and everything is predetermined, how can there be free will? The answer to that is simple: Nothing is predetermined; it is determined, or was determined, or will be determined.

No matter, it all happened at once, in less than an instant, and time was invented because we cannot comprehend in one glance the enormous and detailed canvas that we have been given – so we track it, in linear fashion, piece by piece. Time, however, can be easily overcome; not by chasing the light, but by standing back far enough to see it all at once. The universe is still and complete. Everything that ever was, is; everything that ever will be, is – and so on, in all possible combinations. Though in perceiving it we imagine that it is in motion, and unfinished, it is quite finished and quite astonishingly beautiful.

In the end, or rather, as things really are, any event, no matter how small, is intimately and sensibly tied to all others. All rivers run full to the sea; those who are apart are brought together; the lost ones are redeemed; the dead come back to life; the perfectly blue days that have begun and ended in golden dimness continue, immobile and accessible; and, when all is perceived in such a way as to obviate time, justice becomes apparent not as something that will be, but as something that is.

I first encountered the non-linear interpretation of linear history (so beautifully expressed here by Helperin)in St. Augustine's City of God. It came to life for me, however, in a unique way when I first saw the Pompidou Center in Paris. One rises from floor to floor by escalators encased in plexiglass tubes on the outside of the building. People stretch before and aft in one long line. But from outside, from the plaza, you see all the people at once, all who think they are part of a line are in fact part of a panorama. That's now how I think of time.

ReplyDelete