Betty's Appalachian Sweet Corn Pudding

She

was, without a doubt, the most genuinely kind, sweet, gentle soul I’ve

ever met, so much so that, in my eyes, anyway, she sometimes rounded the

corner of reality and almost became a caricature of herself - even to

her, which made her giggle despite herself. Her husband, on the other

hand, was a rumpled, crumpled, withered shell of a man for whom the

adjective ‘cantankerous’ found a new depth of meaning.

Jack

was my Hospice patient and like many on the Western side of Sussex

County suffered from COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease). After

years of smoking unfiltered Lucky Strike cigarettes and inhaling farm

petrol and Monsanto and God knows what else in the steel mills, his

disease process was now classified as “end stage”. He was on continuous

oxygen therapy, delivered via nasal cannula, and was now receiving

nebulizer treatments - liquid morphine delivered via a supersaturated

mist of water - four times a day.

Like my

experience with many COPD patients, he, as Hospice professionals like to

say, “had a few control issues”. Well, if you aren’t in control of your

breathing, you’d have “control issues,” too. But Jack, well now, Jack’s

issues with control were Black-belt level. He could bark orders laced

with denigrating insults that would make a Drill Sargeant feel like a

novice.

After 54 years of marriage, Betty was a pro

at deflection. She reminded me of Emma Webster, Tweety Bird’s Granny,

who seemed to manage the ongoing war between Sylvester the Cat, Tweety

Bird, and Hector the Bulldog with nonplussed charm and delight. Nothing

ever dampened her spirit.

Unless you crossed her.

And then she could whip out a cast iron skillet from thin air, hold it

up like a stop sign until, as she said in her cheeriest voice, you

“changed your tune,” and then she’d go right back to dusting counters

with the sweetest smile you ever did see, chirping her pleasantries if

only to herself, if need be.

She seemed to be

holding in her heart a secret interior story that she listened to rather

than paying any nevermind to what was going on around her. I suppose,

if she did, she’d just crumble and she knew that was simply not going to

happen. Could not possibly happen. Not in this life.

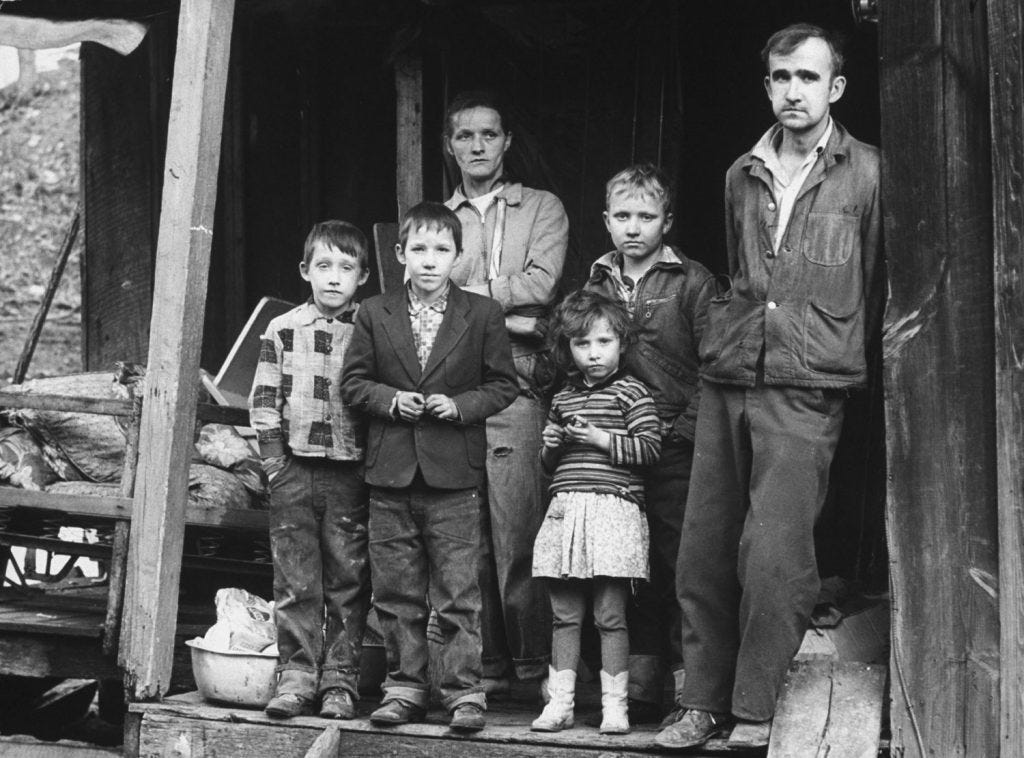

Betty

and Jack were from “dirt poor” but “land tough” Appalachian stock. The

genetics of Scotch-Irish, German, and English people who had fled the

hardships and poverty of Europe, combined with the Native American

tribal communities who had lived there for centuries, gave them not only

the resilience and tough exterior they needed but an internal emotional

and spiritual strength that helped them shape their own Appalachian

culture through language, music, religion, and agriculture. And, food.

More on that in a minute.

”Their people” - both

Jack and Betty’s - had settled in Northwestern Pennsylvania where they

worked the farms and then migrated to the East to work the coal mines or

down to the steel mills in Pittsburgh or the textiles, shipbuilding,

and iron production of Philadelphia. Like our biblical ancestors who

wandered around wherever there was water and grass for their flock, they

moved anywhere there were jobs.

Jack and Betty had

faired pretty well. Jack “lucked out,” Betty said and had gotten a

good-paying job in the steel industry. Betty was able to stay home and

raise their three girls, although she did work part-time in the school

cafeteria when the girls got older. She carefully saved her small salary

as the downpayment for their manufactured home in a trailer park

outside the city limits.

Eventually, as the girls

graduated high school (an accomplishment neither Jack nor Betty had been

able to achieve) and left home, they sold their home in PA and moved to

another manufactured home in Sussex County, Delaware, where the

property taxes were low and the cost of living was more affordable.

The

girls were all married and had kids of their own. They had good

educations and good jobs and had married well. They had good cars and

nice homes and enjoyed wonderful family vacations, living a modest

middle-class life that was well beyond even the wildest dreams of their

parents.

Jack and Betty were very proud of their

family. You’d never know it by Jack, though. He seemed to have been in a

perpetual bad mood for most of his life. One day was particularly bad.

Betty and I had been talking about a documentary she had seen on

television the night before about the slavery of “the Indians and the

Blacks,” she said, “in Appalachia. Can you believe that? Slaves? In

Appalachia?”

”Why,” she said, “I had no idea. I

mean, we were all dirt poor. I didn’t have my own pair of shoes until I

was 14 years old. Mama did her best but life was hard. Slaves? How could

there be slaves? Who had the money to own them?” she asked in the

purest innocent ignorance.

That’s when Jack

exploded. “Oh, you feel bad for the Blacks and the Indians, do you? What

about the White slaves? Huh? What about us? Do you feel bad for White

slaves?”

Betty looked bewildered. “Joseph Arlo Smith, what are you talking about?” she asked.

That’s

when Jack told the story that had been eating at his insides since the

time he was seven years old and his mother died and his father sent him

down to a neighbor’s farm to work his field.

“I was

only seven years old but I worked like a grown man, plowing, planting,

weeding, harvesting. I slept in the barn on the hay, just like the other

work animals, with just a thin blanket to cover me. I ate the leftovers

from the farmer’s table. I ate in the barn, just like the other work

animals. I remembered some of the letters they taught me in school and I

tried to read some, from the newspapers in the trash. I didn’t see my

family except for Christmas and Easter Day.”

Jack

started to have a bit of difficulty breathing. “Jack! Jack! Now, don’t

get yourself all upset. Let me get your rescue inhaler.” Betty said.

Jack shook his head. “No! Don’t give me that. I need you to listen to

me, Betty. I’ve never told you this part before. You need to know this.

You need to listen to this. Ain’t no one heard this before.”

”I

always thought Daddy had sent me there because he couldn’t care for us,

what with Mama gone. One day, the farmer came in and told me to get my

stuff and leave. He couldn’t afford me anymore. And I thought ‘Couldn’t

afford me’? What in the heck was he talking about?”

”So

I walked home and Daddy was waiting for me in the truck. Drove me right

down to another farm on the other side of the county but this time, he

said I wouldn’t be coming home anymore. Not for Christmas. Not for

Easter. This was going to be my new home and I’d better be good and I’d

better work hard and behave.”

”I was 12 years old. I

saw the man give my father some money. And that’s when I figured it

out. I only had a little bit of education. I could read some, but I was

pretty good at reading the writing on the wall. My father had sold me.

He had been collecting my salary from the other farmer. This one had

just bought me outright.”

”Do you know what that

means, woman? White slavery! That’s what it was. White slavery. By my

very own father! So, don’t go talking to me about the poor Blacks this

and the poor Indians that! What about the poor Whites? We was sold into

slavery, too. What about us, huh?”

There was no

discussion this time. Betty got up and got his rescue inhaler. “Here

now, puff on this, Jack, and calm yourself down.”

Jack

took some puffs and then, wiping the tears from his eyes he looked up

at her and said, his voice raspy and his breath labored, “And, you

wondered all those years why I am the way I am. You always asked me why I

couldn’t be more affectionate, especially to the girls. You asked why I

never held your hand. You asked why I always had to be in such a bad

mood all the time. You wondered why I wouldn’t go to church with you,

even on Christmas and Easter, why I didn’t want the chaplain here to

come visit.”

”Well, now you know. How can you show

love when love’s never been shown to you? Why go to church when God

never came to me, not one time in the field when my back was breaking?

Not one time of the many times I cried myself to sleep at night, out in

the barn, sleeping on the hay, with only the animals to hear me?”

”So,

when I was 15 years old, I got up early one morning and walked down to

the stream to wash myself. When I came up out of the water it came to

me. I could just walk away. I could just walk and keep on walking. And

so, I put on my clothes and I did just that and I never looked back.”

”But

somehow, I found you, Betty. I want you to know that you are the one

miracle I ever prayed for. You were more than any miracle I could have

asked for. You gave me three beautiful girls. We have a good life. But,

this . . . stuff . . . being so many years a white slave . . . well,

it’s just been a cancer eating me up all these years. It’s killing me,

Betty. Squeezing the air right out my lungs.”

”So, I

had to get this off my chest. I didn’t mean to. But, you know, with all

this stuff about the Blacks and the Indians . . . . and with the

chaplain here, and all . . .I couldn’t hold it in no more . . . Forgive

me, Betty. That’s what I mean to say. Forgive me, Betty. Understand,

please. I do love you, Betty. You’re the best thing that’s ever happened

to me in my whole life. I don’t want to lose you.”

Jack

could hardly breathe. His lips were turning blue. He was holding on so

hard to the armrest of his chair that his knuckles were white. Betty was

comforting him as she set up his nebulizer. Wiping the sweat from his

brow. Gently stroking his hair, wet with sweat, back from his face.

“There, now. Easy, now. Rest now, Jack.”

After

a few minutes, Jack was breathing easier. He tilted his head back on

the headrest of his recliner as Betty lifted the metal arm on the side

of the chair which lifted his legs. “You stay right here, Jack, and I’ll

fix you something. Okay?”

Jack nodded. Betty

looked at me and said, “I’m going to need your help in the kitchen. You,

my dear, are going to help me make Appalachian Sweet Corn Pudding.”

I

followed her into the kitchen as she spoke, her voice lower than normal

so as not to disturb Jack, but with that same, sweet, kind, gentle lilt

that seemed not to have been disturbed at all by what we had just

heard.

As we busied ourselves opening cans of corn

and creamed corn and getting the eggs and milk from the fridge and the

cornstarch and sugar from the pantry, Betty chatted merrily in her usual

chirpy cadence.

I think I was more stunned than I

realized. Jack’s story had shaken me to my core. The story and the raw

honesty and emotional pain of it all were finally hitting me.

Just

as I opened my mouth, Betty turned to me and said, “We are making

Appalachian Sweet Corn Pudding because that’s the one thing Jack

remembered his mother made and it’s the last thing she made before she

died. I knew it was special to him for that reason, but I . . . I . . .

I had no idea . . . . .”

And, with that, she

collapsed into my arms and cried and heaved and sobbed. I whispered

softly, “Of course you didn’t know. How would you know? He never told

you. I’ve got you, Betty. You go ahead and cry. I’ve got you.”

She

cried and cried some more and then, just as suddenly as she started,

she stopped, took a deep breath, dried her eyes with a tissue she had

retrieved from her pocket, and then shoved it back in, hard. She took

another deep breath, and said, “So, we’re going to make my grandmother’s

Appalachian Sweet Corn Pudding. Because it will make Jack feel better.

It will make Jack know that he is loved. And, because it will help you

know something about my people, and why we may be poor but we are strong

and good and kind.”

”You’ll help me make this,” she

said, in the kindest but firmest directive I think I’ve ever been

given. “I’ll give you my recipe. You’ll go and see Mrs. Jones down the

street and visit with her while the corn pudding cooks. And then, you’ll

come back and have a dish with us. And, you’ll know what love tastes

like.”

In

this morning’s Epistle, St. Paul writes to the beloved people of

Phillipi in Northern Greece from his jail cell in Rome - although some

scholars say Ephesus or Caesarea - somewhere between 60-62 BCE.

He

says something that has always caught me as a most beautiful way to

talk about the power of The Resurrection. “But our citizenship is in

heaven,” he says, adding, “He (Jesus) will transform the body of our

humiliation that it may be conformed to the body of his glory . . . ".

I

think I understood those words much better after I had tasted the first

spoon of Betty’s Appalachian Sweet Corn Pudding. Cynics will say that

it was probably the sugar but I felt instantly transported to my status

as a citizen in heaven.

I also understood why Jack had been so transformed every time Betty made him some sweet corn pudding. For just a few moments, all the years of his humiliation were washed away as the memories of his mother’s love flooded every corner of his being.

“Salvation is of the Lord,” we are taught to say,

meaning that salvation is a gift from God, not earned through human

effort. In the Black church, you’ll often hear folks repeat the words

of Nehemiah, “The joy of the Lord is my strength," meaning that finding

strength and resilience in faith and joy in God's presence is crucial

for navigating life's challenges.

Sometimes, the

gift of salvation comes from unexpected sources. The joy of the Lord can

be found in surprising places. I don’t know this for sure, but I

suspect Jack and Betty were saved, in some small part, by the joy of the

memories of love that were cooked into the Appalachian Sweet Corn

Pudding.

I know I am, every time I eat a spoonful.

Here, try some and see for yourself. It’s delicious as a side dish - I

often make it at Thanksgiving - but it’s fine all by itself. When no one

is looking I even eat spoonfuls of it - cold - right out of the dish in

the refrigerator.

It’s my passport that tells me

that, while I’m here on this earth, I’m just a resident alien. My

Baptismal Certificate is my Green Card. My citizenship is in heaven.

I’m a citizen of heaven. I have tasted love.

Betty’s Appalachian Sweet Corn Pudding

3 eggs

½ cup melted margarine

½ cup white sugar

1 (16-ounce) can whole kernel corn, drained

2 (15-ounce) cans cream-style corn

2 teaspoons cornstarch

½ cup milk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Directions:

Preheat oven to 350 degrees F (175 degrees C). Grease a 9x13 baking dish; set aside.

Beat eggs until fluffy in a large bowl. Stirring constantly, pour in melted margarine. Stir in sugar, whole-kernel corn, and cream-style corn until well combined. Dissolve the cornstarch in the milk; combine with the corn mixture. Stir in vanilla. Pour the mixture into the prepared baking dish.

Bake in the preheated oven until the pudding is

puffed and golden, and a knife inserted into the center comes out clean.

It will take about 1 1/2 hours.

1 comment:

"Such a beautiful and heartfelt reflection. Jack and Betty's story is a touching reminder of love, faith, and the richness of Appalachian heritage. Thank you for sharing this!"**

Post a Comment